Flooring Installation

The best flooring in the world can't do much for you until it's properly installed.

Topics

We share tips for installing a wide range of flooring materials, as well as business insights for installers and contractors.

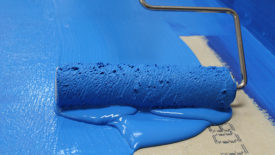

Flooring Installation Products

Information on products for flooring installers and contractors.

Installation Tools & Equipment

Information on tools and equipment that help flooring installers and contractors get the job done.

PAGES

EVENTS

Industry

10/1/24 to 10/3/24

Rosen Shingle Creek

Orlando, FL

United States

CFI + FCICA Annual Convention

Get our new eMagazine delivered to your inbox every month.

Stay in the know on the latest flooring retail trends.

SUBSCRIBE TODAYCopyright ©2024. All Rights Reserved BNP Media.

Design, CMS, Hosting & Web Development :: ePublishing

.png?height=168&t=1713972368&width=275)

.png?height=168&t=1713277515&width=275)